Chip Card Basics

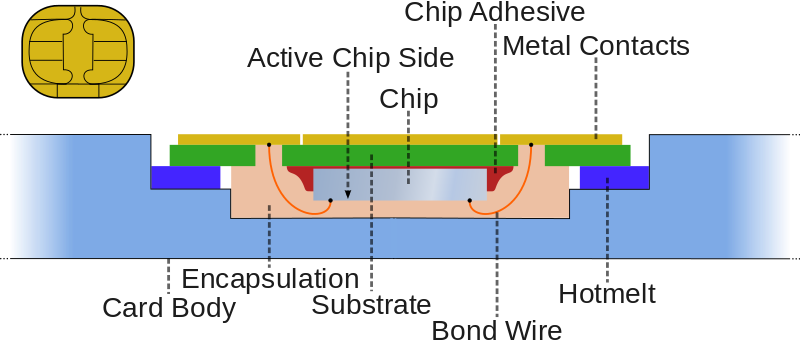

The specifications powering chip and PIN credit cards were first published in 1996. The vernacular for this set of documents is the EMV Chip specifications, named after the three organizations that originally authored it: Europay, MasterCard, and Visa. Credit cards that support this are easily recognizable by the gold-plated contact pads featured on the card. Underneath these pads lies the remainder of the chip assembly.

Justin Ormont / CC-BY-SA-3.0

Justin Ormont / CC-BY-SA-3.0

This chip is powered by the reader device that it’s inserted into. Keep in mind that the specification also outlines contactless payment like the capabilities found in NFC-enabled smartphones. It’s worth clarifying that these are complementary technologies: EMV is a payment technology while NFC is a communication technology that enables contactless EMV.

Why the switch?

While chip cards have long been in use globally, they are only recently making inroads in the United States. Their largest advantage over magnetic strip credit cards is that they are extremely difficult to counterfeit. Magnetic stripe cards contain unencrypted data and can be easily stolen and copied by card skimmers on ATMs or unscrupulous staff during checkout. An additional advantage over the legacy format is that chip cards can’t be demagnetized.

Because of the additional security guarantees that these cards provide, the liability of reimbursing certain fraudulent transactions has shifted to US businesses as of October 1st, 2015. Specifically, businesses are now responsible when a counterfeit of the magnetic stripe from a chip card is used on a terminal that is not enabled for contact chips. All other cases are the responsibility of the card issuer.

And yes, you read that right. Chip cards are still being produced with magnetic stripes so they can work at merchants which have not yet switched over to chip-enabled readers.

How are they more secure?

So, what exactly is in this chip, and what makes it more secure? The chip serves the purpose of authenticating that the card is genuine. The chip contains the same information that the magnetic stripe contains, but it’s encrypted via asymmetric cryptography during the chip creation process. In a nutshell, this means that there is a pair of digital keys that can decrypt what the other encrypts, and vice versa.

The three main pieces of data stored in the chip are:

- account information (e.g. account number, expiration date)

- public key of the card

- public key of the bank (e.g. Wells Fargo)

All three of these pieces of information are hashed and encrypted in the following fashion:

- card’s public key is encrypted by the private key of the bank

- bank’s public key is encrypted by the private key of the card issuer (e.g. Visa)

When a card is inserted into a reader, the following song and dance happens:

- the reader decrypts the public key of the bank using the card issuer’s public key. It verifies the integrity of this key from the hash.

- then, it uses the bank’s public key to decrypt the card’s public key and verifies its integrity against the corresponding hash.

- finally, the reader generates an unpredictable number and encrypts it with the credit card’s public key. It sends this number to the credit card.

- the credit card decrypts the message using its private key and obtains that unpredictable number. It encrypts that number along with its credit card information using its private key.

- the reader decrypts the above information and verifies that the returned number matches what was generated earlier. This confirms that the card has the correct private key.

The astute technologist might point out that if the private key is stored on the card itself, what’s to prevent someone from copying that too? The private key is stored in a special chip that is accessible only by the card itself. Any tampering or out-of-band access results in zeroisation of the key. The PIN associated with the card is stored in a similar fashion.

Drawbacks of the US implementation

Adoption has been slow in the US and many cards won’t get this upgrade until 2017. There are costs for both the card issuers as well as the businesses. The chip cards are much more expensive to produce than their magnetic stripe counterparts. One quick search I did showed the difference in magnitude was dollars versus cents ($2 versus $0.15). However, these costs would most likely be offset by reduction in fraud. On the other side, businesses have to buy EMV-compliant readers, which cost around $200.

Sadly, the standard pushed for in the States is the chip and signature technology as opposed to the chip and PIN technology. This means that while your card can’t be duplicated, it can still be stolen and used. The PIN adds an additional layer of security by requiring the cardholder to know the PIN the card was initialized with.

And alas, these security measures only apply to transactions where the card must be physically present. Therefore, fraud through payment vectors like the phone and Internet aren’t any more secure.

References

For further reading, check the following links: