Taking Out The Trash

Suppose you have in your freezer, a lovely frozen burrito wrapped in flexible plastic. After you unwrap it to be microwaved, you’re presented with a choice. What should you do with the wrapper?

- pick it up and place it in the trash can. I run a clean house!

- just leave it on the counter. Someone else will take care of it.

And there you have it, you’re halfway there to understanding the two styles of memory management in programming languages: manual and automatic.

Why Memory Management?

Memory management is extremely important for software. Software is allocated a finite amount of memory by the operating system and it cannot consume more than the system has. Because, physics. Once a running program is out of memory, the program cannot continue to run. It must abort. There is no recourse.

This is akin to trying to move a very necessary piece of furniture, like a bed, into a room with no space for it. If everything in that room is already deemed necessary, you’re plain out of luck.

So, this is why we do the dance of memory management. It is to make space for objects necessary to the continued and correct operation of a software program.

Manual Versus Automatic

Existing implementations of memory management sit on a spectrum between manual and automatic. C is a language which requires manual allocation and deallocation. Java is one of the most popular languages that utilizes automatic memory management as part of the JVM. Some programming languages, like D, offer a hybrid approach.

Both styles of memory management are responsible for two tasks:

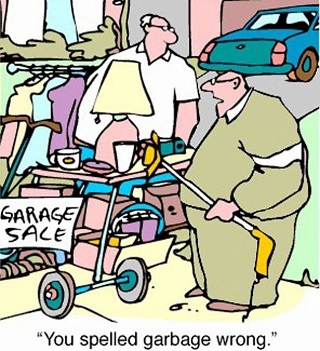

- determining which objects are no longer in use (garbage identification)

- reclaiming the space used by the garbage (garbage collection)

Manual

The most significant advantage of manual memory management is that both garbage identification and collection are easy to do. It is specified explicitly in code. This offers a huge performance increase compared to the automatic approach. Therefore, it’s a natural choice for real-time systems. This performance comes at the risk of introducing issues such as memory leaks or double-free bugs. Therefore, most software benefits from automatic memory management.

Automatic

Relinquishing memory management to another system allows you to focus on writing core logic for your software instead of worrying about when you have to allocate memory, how much to allocate, and when it should be deallocated. A memory manager helps address these concerns. It’s able to automatically determine which objects are no longer in use and will never be used again. This can be tough to determine manually in complex systems. It can also determine the most appropriate time to get rid of that object. For example, when the system isn’t under heavy load. Note that memory leaks can still occur if garbage can’t be accurately identified.

However, there is a performance penalty for using a garbage collector. It comes from the work necessary to perform garbage identification and collection. Algorithms are discussed below.

Garbage Collection Algorithms

-

Do nothing. Simply do nothing at all and just let the number of objects pile up. As odd as it sounds, this is an appropriate strategy for certain operations which have a finite run time. Once execution finishes, everything associated with it can be thrown out. This may be appropriate for a server thread associated with a web request where a run of the garbage collector would be noticeable. If you insist on a metaphor, this is like a waiter clearing your table off only at the end of a meal instead of removing plates the moment you’re done with them.

-

Reference counting. Every time a piece of code gets its hands on an object, an internal counter on that object goes up. When it’s done with that object, the counter goes down. Once that object is no longer used, as indicated by a 0-value on that counter, it is destroyed.

-

Mark and sweep. All of the objects that are in use are marked. This is done by starting at a root object, such as a thread, and following object references. Once all objects are marked, all non-marked objects (i.e. the unused objects) are removed. One of the side-effects of this operation is that objects become fragmented across the heap space and the memory manager needs to fit new objects into the holes created from object allocation.

-

Mark and compact. This is a variation on the mark and sweep algorithm where the memory is now compacted after the sweep operation. This makes future memory allocation cheap. However, the compaction operation can be expensive.

-

Mark and copy. This is the basis for generational garbage collectors. As before, all live objects are marked. However, instead of removing unused objects, the live objects are copied into a new area of the heap. This forms a new generation. All of the object references are then updated. The heap area where garbage collection was just run can now be completely obliterated and memory can be allocated contiguously in that section again. Each subsequent generation will have garbage collection run on it less and less frequently. This algorithm is based on the assumption that most objects are short-lived. This is similar to what Java uses.

Further Reading

If you’re interested in learning more about garbage collection, check the following articles: